In this article we give a brief overview of the history of interstellar studies. The entire field would encompass perhaps 10,000 papers and so inevitably this overview is not complete. Instead, this is intended to give just a flavour for some of the progress in the field and the directions it has taken in considering travelling to other star systems.

In 1952 the British scientist Les Shepherd published a paper in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society titled Interstellar Flight [1], in which the author first described the essential requirements for an interstellar mission as implied by basic rocketry principles. The author also covered area such as erosion of the spacecraft due to particle bombardment due to interactions in the interstellar medium.

In 1960 the american physicist Robert Bussard made an amazing proposal which appeared to present a clear method of travelling between the stars. His paper Galactic Matter and Interstellar Flight [2] suggested that a spacecraft could get away from having to carry enormous amount of propellant fuel by instead mining the fuel en-route. In particular this was the hydrogen fuel of the interstellar medium. In principle such a vehicle would be capable of reaching relativistic speeds. Subsequent research however pointed out some of the technical issues with trying to make an interstellar ramjet work, such as the low abundance of hydrogen in the interstellar medium, the small cross section of hydrogen to fusion capsule, the overheating of the protons within the large magnetic funnel. It was clear therefore that if any version of the ramjet was possible, it would involve moderating those protons to managable energies.

In the early 1980s the american physicist Robert Forward pursued the idea of propellantless propulsion, such as in his paper Rountrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails [3]. His interest focussed on the idea of using directed energy beaming, such as with microwave beams or optical lasers, to push a small sail craft to the stars at large speeds. This culminated in his Starwisp concept in his paper Starwisp: An Ultra-Light Interstellar Probe [4]. On paper the energy beaming concepts proposed by Forward looked highly credible, but they came with the disadvantage of requiring large amounts of power, typically in the 10s TW levels. Forward was very optimistic about the potential of his ideas and even presented his concepts as a potential roadmap program to the US Congress. This was captured in his earlier paper A Programme for Interstellar Exploration [5], in which he believed it was possible to launch such missions by the year 2000. Forward remained an advocate for interstellar studies for many years, and he also initiated a form an index for Interstellar Travel and Communications: A Biography [6].

As well as the progress in thinking about propulsion, other work also focussed on the possibility of finding extra-terrestrial life assuming starships could be constructed by us or others that could eventually travel around the galaxy. The american astronomer Carl Sagan wrote about this in Direct Contact Among Galactic Civilizations by Relativistic Interstellar Spaceflight [7] as well as Galactic Civilizations: Population Dynamics and Interstellar Diffusion [8]. In this work Sagan proposed it was possible travelling at relativistic speeds to reach the centre of the galaxy in only 28 years and the edge of the Andromeda galaxy within 32 years and the centre of the known universe within 48 years. He also wrote about the possibility of trying to detect other intelligent life in the galaxy, such as in On the Detectivity of Advanced Galactic Civilizations [9].

In the 1950s and 1960s , former members of the Manhattan project to build an atomic bomb, came together to consider whether such technology could be utilised for the application of space propulsion. This was conducted under a General Atomics / United States Air Force study called Project Orion. This was based on an original proposal from Ulam and Everett in their work On A Method of Propulsion of Projectiles by Means of External Nuclear Explosions [10]. The work suggested that using atomic bombs or hydrogen bombs it may be possible to achieve speeds of 5% and 10% of the speed of light respectively. The British born physicist Freeman Dyson wrote about the project in Death of a Project [11] and Interstellar Transport [12]. An excellent history of Project Orion was written up in Project Orion: The Atomic Spaceship 1957 - 1965 [13]. An excellent review of nuclear pulse propulsion was written by the British scientist Anthony Martin in Nuclear Pulse Propulsion: A Historical Review of an Advanced Propulsion Concept [14].

Despite the large growth in research into the question of intelligent life in the galaxy, the consensus view was that we didn’t see any. This bought about the possibility that interstellar travel was not possible. To address this, the British scientist Anthony Martin and engineer Alan Bond initiated a study of the British Interplanetary Society called Project Daedalus. They assembled a team and over 5 years designed a two-stage fusion based concept that would reach 12% of light speed and be sent as a 450 tons robotic flyby probe to the Barnard’s star system 5.9 light years distance. The spacecraft would carry 50,000 tons of D-He3 fuel and it utilised an inertial confinement fusion concept as its ignition system, based on a paper the team had read published by the German born physicist Freidwardt Winterberg titled Rocket Propulsion by Thermonuclear Microbombs Ignited with Intense Relativistic Electron Beams [15]. The study was highly rigorous in that it encompassed all of the essential systems of starship design, including propulsion, power, structure, materials, navigation, mission analysis, reliability, particle bombardment and more. It remains the most comprehensive starship design concept in history. The results of the study were eventually published as Project Daedalus: The Final Report on the BIS Starship Study [16].

The same authors that had initiated the Project Daedalus study had also initiated a study of a world ship. This is an enormous vessel that can carry large populations of people and typically travels at a speed of 1-3% of the speed of light. The results of this work was published in World Ships - An Assessment of the Engineering Feasibility [17] and World Ships - Concept, cause, Cost, Construction and Colonisation [18]. These concepts were nuclear pulse propulsion based. To provide a counter perspective, the american physicist Gregory Matloff wrote about world ships that did not utilise nuclear power and propulsion. In particular in his work titled Interstellar Solar Sailing: Considerations of Real and Projected Sail Materials [19] had already advocated for the use of solar sail systems in the transport of spacecraft around the Solar System, and so applying them to interstellar spacecraft was an extension of this work, which he did in Faster Non-Nuclear World Ships [20]. Matloff also wrote several books, including the outstanding Starflight Handbook [21].

In the modern era there has been a revival of the subject of interstellar studies. One of the causes of this has been the discovery of extra-solar planets around other stars, which now number thousands. In the 1990s the american space agency NASA began looking at methodologies in Breakthrough propulsion, such as work by the american scientist Marc Millis in Challenge to Create the Space Drive [22] and Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Workshop Preliminary Results [23]. A lot of these ideas were later published in the excellent book Frontiers of Propulsion Science [24].

Research that started to gather greater interest in breakthrough ideas included extensive theoretical work on wormhole theories by people such as the american physicist Kip Thorne in his work Wormholes in Spacetime and their Use for Interstellar Travel: A Tool for Teaching General Relativity [25]. In addition, a post-graduate student then at Cardiff University, Miguel Alcubierre wrote a paper titled The Warp Drive: Hyper-Fast Travel within General Relativity [26] in which he demonstrated theoretically how it may be possible to one day move space and so move around the Cosmos in the manner described by the science fiction show Star Trek.

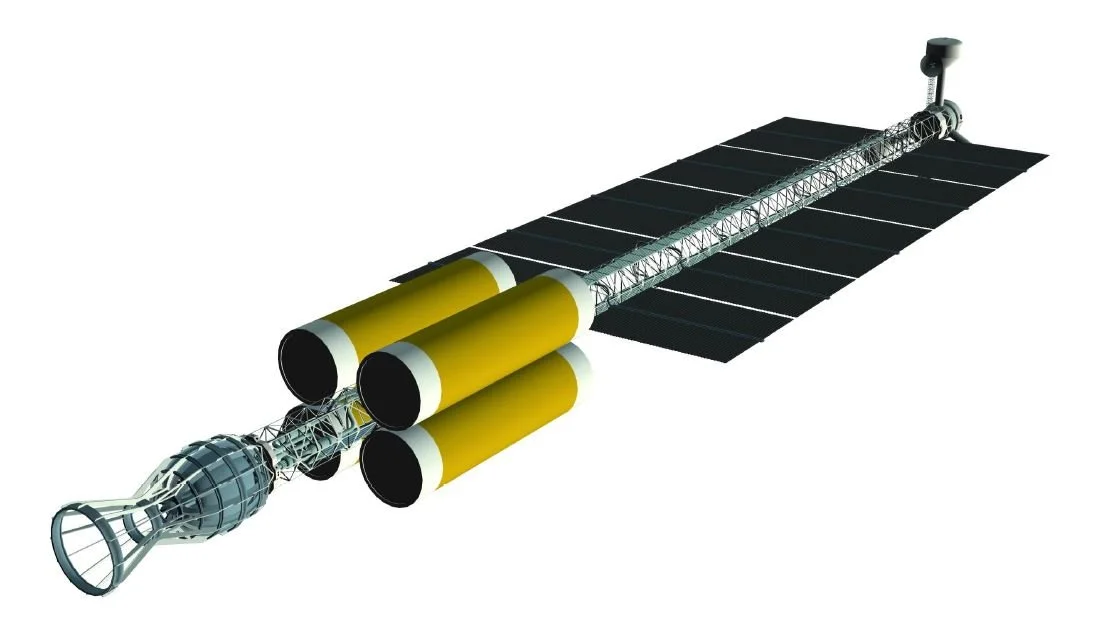

The Project Daedalus study has received a revival known as Project Icarus, and a study was initiated in 2009 as written in the paper Project Icarus: Son of Daedalus - Flying Closer to Another Star [27]. The study was initiated by the British physicist Kelvin Long who also went on to write a book about interstellar space propulsion titled Deep Space Propulsion, A Roadmap to Interstellar Flight [28]. The Project Icarus study is different from the original Project Daedalus study, in that it aims to demonstrate theoretically full orbital insertion into the target stellar system, as opposed to Daedalus which was a flyby probe only. The study has resulted in many concept designs, with the most advanced being the Firefly concept, as published in Plasma Dynamics in Firefly’s Z-Pinch Fusion Engine [29].

Many of the papers in this field have been published in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, with its red covered interstellar issues published between 1974 - 1991 and revised recently. The British Interplanetary Society was set up in 1933 and is one of the world’s oldest space societies. It has been the torch bearer of the interstellar vision since its founding, and in particular since that first Les Shepherd paper in 1952.

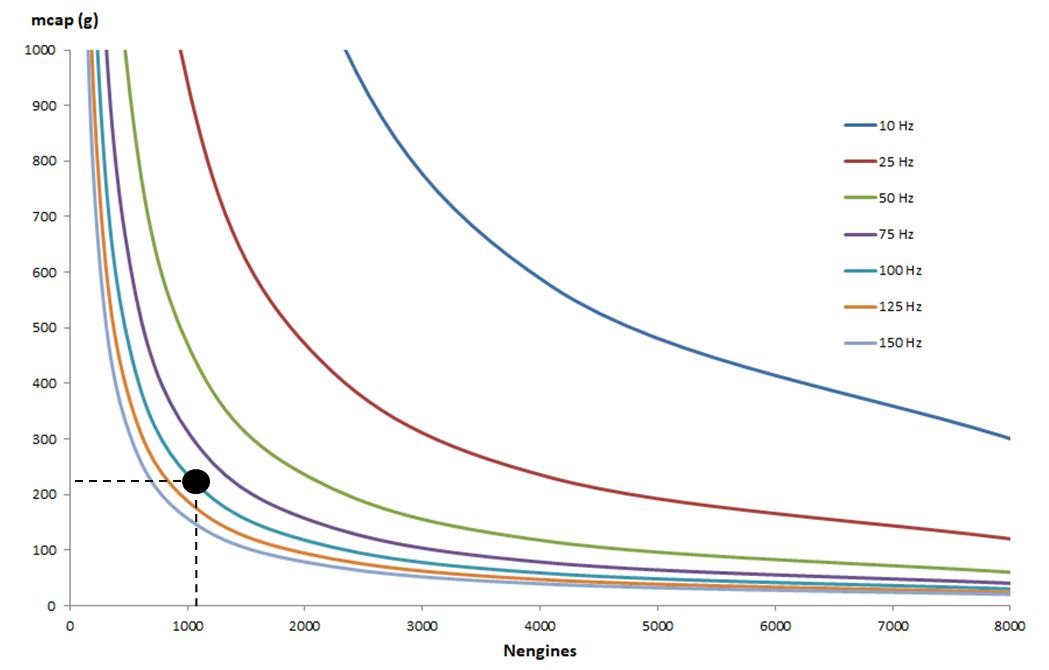

Today there are many organisations pursuing the interstellar vision. This includes the Tau Zero Foundation, the Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop, Icarus Interstellar and the Initiative for Interstellar Studies (also known as the Institute for Interstellar Studies in the United States). The most recent inclusion to this list is the Breakthrough Initiatives, an organisation that has been funded in the millions of dollars and is directly pursuing both the detection of intelligent life in the Universe, but also under its Project Starshot it is pursuing the design and launch of an interstellar probe within two decades. This initiative was instigated by the american physicist Philip Lubin in his paper A Roadmap to Interstellar Flight [30] and is an effort to send something that is Gram-scale in mass by the use of directed energy laser beam propulsion.

In addition to all of the technical publications, a parallel stream of thought that has helped to move the field forward has been the science fiction literature. In particular, authors such as Robert Heinlein in his Time for the Stars [31] which explored torch ship propulsion and relativistic flight; Poul Anderson in his Tau Zero [32] which explored interstellar ramjets; Arthur C Clake in his The Songs of Distant Earth [33] which explored quantum vacuum propulsion; or Clarke again his now famous 2001 A Space Odyssey [34] which explored von neumann probes and extraterrestrial intelligence in the Universe. The book was made into a film of the same name, directed by Stanley Kubrick; Robert Forward in his The Flight of the Dragonfly [35] which explored laser sail propulsion; Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle in The Mote in God’s Eye [36] which explored laser sail propulsion but also the first contact with an alien civilisation. These are just a small example of the vast literature on this subject.

This brief history of interstellar studies has barely scratched the surface on what has been achieved. It is not possible in these pages to list everything, but suffice it to say good progress has been made theoretically and now the effort needs to move towards experimental demonstrations and actual in-flight experience. The Foundations of Interstellar Studies workshops are designed to help move us along this trajectory with a focus on problem solving and solutions.

References

[1] L. R. Shepherd, Interstellar Flight, JBIS, 11, 4, July 1952.

[2] R. W. Bussard, Galactic Matter and Interstellar Flight, Astronautica Acta, 6, Fasc.4, 1960.

[3] R. L. Forward, Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser-Pushed Lightsails, J.Spacecraft & Rockets, 21, March-April 1984, pp.187-195.

[4] R. L. Forward, Starwisp: An Ultra-Light Interstellar Probe, J.Spacecraft, 22, 3, May-June 1985.

[5] R. L. Forward, A Programme for Interstellar Exploration, JBIS, 29, pp.610-632, 1976.

[6] E. F. Mallove, R. L. Forward et al., Interstellar Travel and Communication: A Bibliography, JBIS, 33, pp.201-248, June 1980.

[7] C. Sagan, Direct Contact Among Galactic Civilizations by Relativistic Interstellar Spaceflight, Planet. Space Sci, pp.485-498, 11, 1963.

[8] W. I. Newman & C. Sagan, Galactic Civilizations: Population Dynamics and Interstellar Diffusion, Icarus, 46, pp.293-327, 1981.

[9] C. Sagan, On the Detectivity of Advanced Galactic Civilizations, Icarus, 19, pp.350-352, 1973.

[10] C. J. Everett & S. M. Ulam, On a Method of Propulsion of Projectiles By Means of External Nuclear Explosions Part 1, LANL, August 1955.

[11] F. Dyson, Death of a Project, Science, 149, 3680, pp.141-149, 9 July 1965.

[12] F. Dyson, Interstellar Transport, Physics Today, 21, 10, pp.41-45, October 1968.

[13] G. Dyson, Project Orion: The Atomic Spaceship 1957 - 1965, Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 2002.

[14] A. R. Martin & A. Bond, Nuclear Pulse Propulsion: A Historical Review of an Advanced Propulsion Concept, JBIS, 32, 8, pp.283-310, August 1979.

[15] F. Winterberg, Rocket Propulsion by Thermonuclear Microbombs Ignited with Intense Relativistic Electron Beams, Raumfahrtforschung, 15, pp.208-217, 1971.

[16] A. R. Martin, A. Bond, Project Daedalus - The Final Report on the BIS Starship Study, JBIS Supplement, 1978.

[17] A. Bond, A. R. Martin, World Ships - An Assessment of the Engineering Feasibility, JBIS, 37, pp.254-266, June 1984.

[18] A. R. Martin, World Ships - Concept, Cause, Cost, Construction and Colonisation, JBIS, 37, pp.243-253, June 1984.

[19] G. L. Matloff, Interstellar Solar Sailing: Considerations of Real and Projected Sail Materials, JBIS, 37, 3, pp.135-141, March 1984.

[20] G. L. Matloff, Faster Non-Nuclear World Ships, JBIS, 39, 11, pp.475-485, November 1986.

[21] E. Mallove and G. Matloff, The Starflight Handbook: A Pioneer’s Guide to Interstellar Travel, John Wiley & Sons, 1989.

[22] M. G. Millis, Challenge to Create the Space Drive, Journal of Propulsion and Power, 13, 5, pp.577-582, Sept/Oct 1997.

[23] M. G. Millis, Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Workshop Preliminary Results, NASA/TM-97-206241, November

[24] M. G. Millis and E. W. Davis, Frontiers of Propulsion Science, Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics, 227, The American Institute of Aeronautics & Astronautics, 2009.

[25] M. S. Morris and K. S. Thorne, Wormholes in Spacetime and their Use for Interstellar Travel: A Tool for Teaching General Relativity, Am. J. Phys, 56, 5, May 1988.

[26] M. Alcubierre, The Warp Drive: Hyper-Fast Travel Within General Relativity, Class. Quantum Grav, 11-5, L73-L77, 1994.

[27] K. F. Long, M. Fogg, R. Obousy, A. Tziolas, A. Mann, R. Osborne, A. Presby, Project Icarus: Son of Daedalus - Flying Closer to Another Star, JBIS, 62, 11/12, pp.403-414, Nov/Dec 2009.

[28] K. F. Long, Deep Space Propulsion: A Roadmap to Interstellar Flight, Springer, 2011.

[29] R. M. Freeland, Plasma Dynamics in Firefly’s Z-pinch Fusion Engine, JBIS, 71, pp.288-293, 2018.

[30] P. Lubin, A Roadmap to Interstellar Flight, JBIS, 69, pp.40-72, 2016.

[31] R. Heinlein, Time for the Stars, Gollancz, 1963.

[32] P. Anderson, Tau Zero, Doubleday, 1970.

[33] A. C. Clarke, The Songs of Distant Earth, Del Rey Books, 1986.

[34] A. C. Clarke, 2001 A Space Odyssey, Del Rey Books, 1968.

[35] R. L. Forward, The Flight of the Dragonfly, Pocket Books, 1984

[36] L. Niven & J. Pournelle, The Mote in God’s Eye, Simon & Schuster, 1974.